Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Night Sky

- Thread starter Roccus7

- Start date

Hopefully they can detect the larger ones - the US will get blamed for any missed strikes

www.space.com

www.space.com

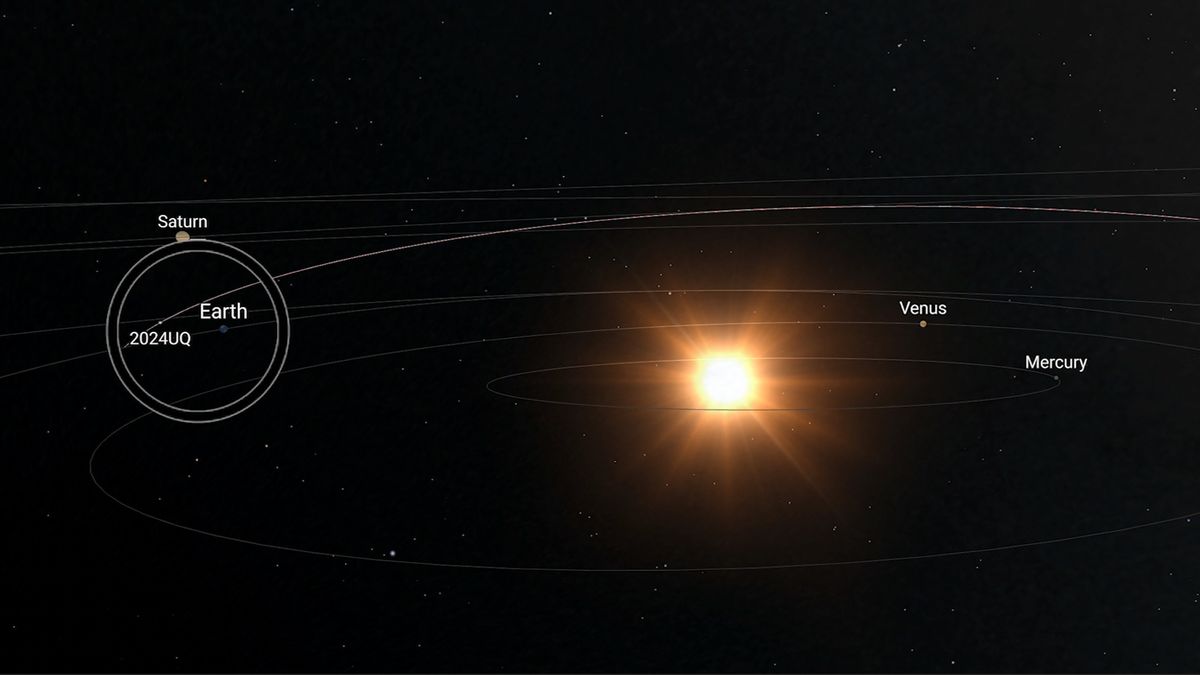

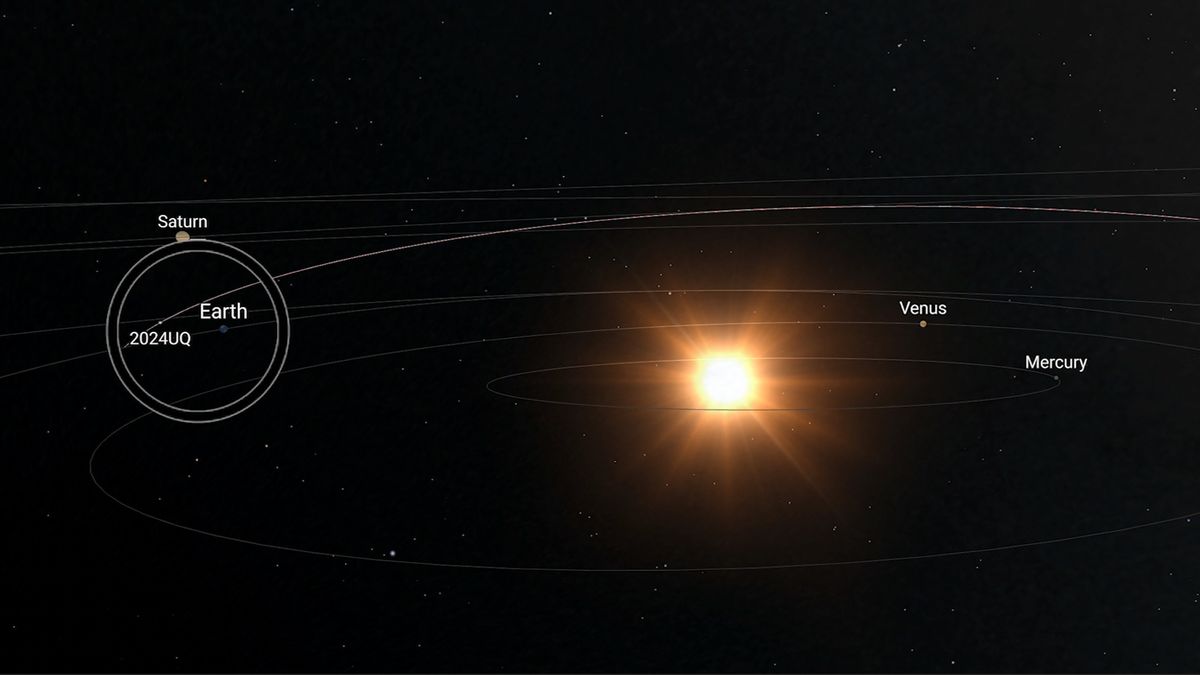

An asteroid hit Earth just hours after being detected. It was the 3rd 'imminent impactor' of 2024

"By the time the astrometry reached the impact monitoring systems, the impact had already happened."

Article with a few stunning professional photos from the space station....

Last edited:

wader

Well-Known Angler

'Unlike anything we have seen before': Astronomers discover mysterious object firing strange signals at Earth every 44 minutes

ASKAP J1832-0911, which is periodically throwing out pulses of radio waves and X-rays, could be a brand-new cosmic object.

wader

Well-Known Angler

Interesting read..............

www.yahoo.com

www.yahoo.com

The Interstellar Visitor Hurtling Toward the Center of Our Star System Is Unimaginably Ancient, Scientists Say

Astronomers recently confirmed that a mysterious object, dubbed 3I/ATLAS came from interstellar space, blowing through the outer solar system at extremely high speeds. It's only the third confirmed interstellar object to have reached our corner of the galaxy, following 'Oumuamua, which was...

Matts

Angler

At 13 billion years old, it's back must be REALLY stiff in the morning!Interesting read..............

The Interstellar Visitor Hurtling Toward the Center of Our Star System Is Unimaginably Ancient, Scientists Say

Astronomers recently confirmed that a mysterious object, dubbed 3I/ATLAS came from interstellar space, blowing through the outer solar system at extremely high speeds. It's only the third confirmed interstellar object to have reached our corner of the galaxy, following 'Oumuamua, which was...www.yahoo.com

wader

Well-Known Angler

Mysterious Object Hurtling Toward Us From Beyond Solar System Appears to Be Emitting Its Own Light, Scientists Say

Last month, astronomers made an exciting discovery, observing an interstellar object — only the third of its kind ever observed — hurtling toward the center of the solar system. The object, dubbed 3I/ATLAS, has caught the attention of Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb, who has a long track record of...

wader

Well-Known Angler

There’s Something Really Suspicious About the Way This Star Died

Stellar death is a complex and mysterious process — but in the case of supernova 2023zkd, things were more gruesome than any astronomer had ever seen before. As its name suggests, this supernova — the fabulous astronomical term for the explosive death of a star — was first spotted back in 2023...

wader

Well-Known Angler

The Black Hole That Could Rewrite Cosmology

Astronomers see a mysterious object shining in the deep sky. It could be older than the stars.

wader

Well-Known Angler

Rogue planet has a record growth rate of 6.6 billion tons per second

Astronomers have observed a massive growth rate in a free-floating rogue planet that’s gobbling up gas and dust at a record rate of 6.6 billion tons per second.

wader

Well-Known Angler

NASA's Voyager 1 Revealed A Stunning Discovery At The Edge Of Our Solar System

Voyager 1 has been exploring the cosmos for decades, but when it reached the edge of the solar system, it found something very strange and very hot.

Two Comets Are Moving Into Your Night Skies in October: How to Watch

The comets A6 (Lemmon) and R2 (SWAN) are visitors from the chilly fringes of our solar system, and could even be visible at the same time.If you like comets, this month is shaping up to be a good season. An assortment of the objects are passing through our cosmic neighborhood, trailed by wisps of gas and dust. This month, skywatchers in the Northern Hemisphere will have the opportunity to observe not one but two once-in-a-lifetime comets in the fall skies.

The celestial visitors, known to scientists as C/2025 A6 (Lemmon) and C/2025 R2 (SWAN), traveled here from the very edges of the solar system where the sun appears as a pinprick of light in the darkness.

A6 (Lemmon) was spotted in January by the Mount Lemmon Survey, which catalogs near-Earth objects from a mountaintop observatory in Arizona.

R2 (SWAN) turned up in early September and is more of an unexpected visitor. It was discovered by Vladimir Bezugly, an amateur astronomer in Ukraine. He found the object in publicly available images from SWAN, or the Solar Wind Anisotropies instrument of the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, a spacecraft stationed nearly a million miles from Earth.

The comet “caught everybody by surprise,” said Quanzhi Ye, an astronomer at the University of Maryland. That’s because the comet arrived from the direction of the sun, a trajectory that kept the object hidden in the glow of our star during its approach, out of view from sky-scanning telescopes around the world.

What is a comet?

Comets are ancient chunks of ice and rock, leftovers from the creation of the solar system. During an encounter with the sun, a comet gets warmed up. Some ice sublimates into gas, which streams away into space, dragging along dust from the object and producing a shimmery tail.When will R2 (SWAN) be visible?

After dazzling stargazers in the Southern Hemisphere, R2 (SWAN) is starting to swing into view in the northern evening sky this week and will remain visible until the end of October.To spot the comet, astronomers recommend going to a dark location with an unobstructed view to the southwest and with as little light pollution as possible. The comet’s brightness is expected to remain out of range of the naked eye, so you’ll need binoculars or a small telescope. About 45 minutes to one hour after sunset, scan low along the horizon. The comet will appear as a “fuzzy ball,” said Yoonyoung Kim, a comet researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Mr. Ye suggests a trick for locating it with your smartphone: Set the camera exposure to a few seconds and take some pictures of the sky.

Astronomers expect observing conditions for R2 (SWAN) to steadily improve until the comet makes its closest approach to Earth on Oct. 20. The object will move higher in the sky each night, toward the darkness and away from the lingering glow of the setting sun.

Comets are as unpredictable as cats, as the astronomy adage goes: They too have tails, and tend to do whatever they want. That means R2 (SWAN) may further surprise us: It brightened considerably when first discovered, and could undergo a similar outburst, perhaps even enough to be visible without binoculars, Mr. Ye said.

There is also the possibility that the comet could disintegrate entirely.

“We are all wondering what it’s going to do next,” he added.

How do I see A6 (Lemmon)?

A6 (Lemmon) is currently gracing the northern morning sky. To observe the comet, you’ll need binoculars or a small telescope — and the fortitude to wake up before dawn.Look for a fuzzy object in the northeast, several hours ahead of sunrise, just below the ladle-shaped Big Dipper. From Earth’s perspective, A6 (Lemmon) will perform a switcheroo halfway through the month, appearing in the evening sky in the west. If predictions hold, A6 (Lemmon) will brighten in late October and early November, possibly enough to be spotted with the naked eye in very dark conditions.

Will it be possible to see both comets at once?

Stargazers could potentially spot both comets sometime around Halloween, said David Dickinson, an amateur astronomer and author of “The Backyard Astronomer’s Field Guide.”A6 (Lemmon) will closely hug the horizon, though, and could be swallowed up by twilight, Mr. Dickinson said. R2 (SWAN) will hover in the sky for hours after sunset, so that comet may be your best bet for an evening dose of cosmic wonder.

Where did these comets come from?

Far-flung comets like these two originate in the Oort cloud, a bubble-shaped realm of frozen objects that surround the solar system at its very edges. According to Carrie Holt, an astronomer at Las Cumbres Observatory in California, such comets are likely “perturbed inward to the inner solar system a very, very, very long time ago,” perhaps jostled by a passing star or the galactic tides of the Milky Way.According to astronomers’ latest calculations, A6 (Lemmon) circles the sun about every 1,351 years, while R2 (SWAN) completes its loop in 642 years.

Other comets reside closer in, within the Kuiper belt region beyond Neptune, and usually take less than 200 years to orbit the sun. Still other comets arrive from interstellar space, such as 3I/ATLAS, which is zooming through the inner solar system now but will be on the wrong side of the sun for viewing this month.

For comet researchers, visits from the Oort cloud are drive-by lessons in cosmic history. Because of their lack of exposure to the sun, these comets contain materials that remain as pristine as they were more than four billion years ago. That offers scientists a glimpse of our celestial beginnings.

If they don’t disintegrate, both comets will return to the chilly hinterlands of the solar system, permanently altered by their sojourn past the sun.

Out there, “it’s actually pretty boring because it’s cold, and there’s not much going on,” Mr. Ye said. This flyby of Earth may be the most exciting thing that has happened to these comets in decades, and it is unfolding right overhead, Mr. Ye said, “so why not just go see?”

wader

Well-Known Angler

Astronomers discover most powerful "odd radio circle" twins ever detected

"Odd radio circles" are enormous and unexplained phenomena that can only be detected using radio telescopes.

WhatKnot

Well-Known Angler

These are Entrepreneurs at their best. Talk about a niche market

Uh oh....

nypost.com

nypost.com

Manhattan-sized interstellar object 3I/ATLAS emitting metal alloy never seen in nature: Harvard scientist

New images of the 33-million ton interstellar object confirmed it is releasing a nickel alloy commonly used in the aerospace industry, Harvard astrophysicist Dr. Avi Loeb revealed.

Latest articles

-

Abu Garcia's Beast SeriesAbu Garcia's Beast Series: Revolutionary Equipment for the Modern Swimbait Revolution October...

- george

- Updated:

- 6 min read

-

World's Lightest Spinning ReelGame-Changer or Gimmick? The Daiwa LUVIAS ST Claims to Be the World's Lightest Spinning Reel An...

- george

- Updated:

- 4 min read

-

New York Fluked Itself!Fluke Management in 2025: Regulators Got It Wrong Halfway through this season New York anglers...

- george

- Updated:

- 2 min read

-

Hunting Stripers and Blues from Rockaway Beach to Moriches InletThe Western Run: Hunting Stripers and Blues from Rockaway Beach to Moriches Inlet By: A Die-Hard...

- george

- Updated:

- 10 min read

-

Surf Fishing for Stripers - The East EndThe Eastern Edge: Mastering Montauk to North Fork Waters During the Fall Blitz By Captain Mike...

- george

- Updated:

- 10 min read