continued from above:

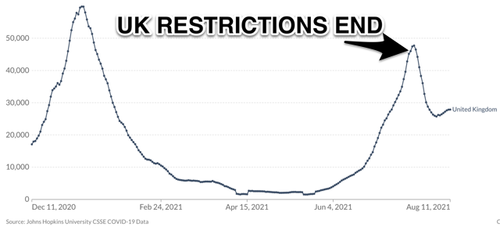

Levitt isn’t the only reputable scientist who sees little if any correlation between government-imposed NPIs and Covid-19 trajectories.

"We’ve ascribed far too much human authority over the virus," said Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, in a recent interview with the

New York Times. "These surges have little to do with what humans do. Only recently, with vaccines, have we begun to have a real impact."

"We had record high cases, hospitalizations and deaths in January, followed by a precipitous decline throughout February and into March…

this does not reflect anything to do with…human mitigation. This is the natural ebb and flow of the virus we’ve seen time and again around the world," said Osterholm on his

Covid-19 podcast.

In that vein, those who exclusively attribute today’s surging case counts in southern states to lagging vaccination rates and purported local mismanagement should note that:

- The southern wave’s timing roughly parallels the region’s 2020 summer surge, which should prompt consideration that seasonality—alongside Delta’s greater transmissibility among even the vaccinated—may be the dominant driver

- While Florida is considered the new epicenter of the pandemic, the state’s vaccination rate matches the national average

- Oregon, despite an above-average vaccination rate, is experiencing its own sharp spike—but has been spared the kind of contemptuous scorn that journalists and Democratic politicians heap on Republican-led Florida

Every NPI Deserves Scrutiny

Over the course of the pandemic, some anti-Covid-19 measures have fallen out of favor in light of new findings and observations. For example, with the understanding that

surface transmission of Covid-19 is extremely unlikely, far fewer people are wiping groceries with Clorox.

Perhaps because they’re bolted into place, the nation’s thicket of plexiglass dividers have shown more staying power, despite research indicating they may not only be futile,

but could actually be making matters worse by thwarting ventilation. In March, the CDC

withdrew its recommendation for barriers on school desks, but has apparently stopped short of discouraging their broad use elsewhere.

Though it’s now socially acceptable to question the use of disinfectants and plexiglass, questioning masks can get you suspended from social media and tarred as a promoter of disinformation—even when you’re

citing peer-reviewed

studies. However, with other widely-embraced mitigation measures fading in light of new data, intellectually honest people should be equally open to the question of whether widespread face-covering—particularly with anything other than an N-95 mask—is worthwhile.

That forbidden discussion is starting to creep into

mainstream media. In a recent appearance

on CNN, the University of Minnesota’s Osterholm—a former Covid-19 advisor to President Biden—caused a

stir by saying,

"We know today that many of the face cloth coverings that people wear are not very effective in reducing any of the virus movement in or out." That’s because Covid-19 particles are astoundingly small. Hard as it to imagine, the imperceptible gaps in surgical masks can be

1,000 times the size of a viral particle. Gaps in cloth masks are well larger than that.

Osterholman has offered a highly relatable standard by which to judge if a particular face covering serves as a meaningful barrier against particles that small: "If you were in a room with somebody smoking, would you smell it in your device that you are using?" That standard not only eliminates cloth masks, but surgical ones too.

Beyond the realities of nanoparticle science and the conclusions of previous

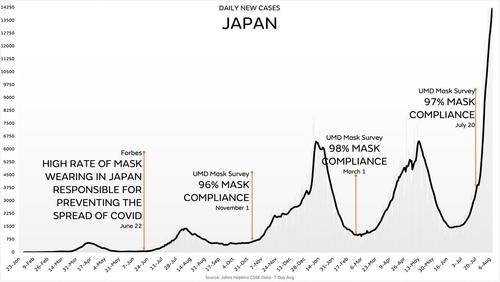

studies, the case for masking is undermined by what we’ve observed during the pandemic.

Sweden, for example, never widely embraced masking. While its per capita Covid death count is well higher than neighboring Finland and Norway, it’s the

15th lowest out of the 31 European Union countries and the UK.

If face-covering were such an essential life-saving practice, Sweden wouldn’t be found in the middle of the EU pack. It would be dead last. That said, using Covid-19 death counts alone to evaluate outcomes is

problematic. Different testing protocols can mean an individual would be positive in one country and negative in another. Jurisdictions also differ in what exactly comprises a Covid-19 death—was it a death

from Covid or merely

with Covid?

More importantly, though, when we solely focus on Covid-19 deaths, we ignore the suicides, fatal overdoses and other unintended deaths that result from the lockdowns themselves. That’s why it’s best to compare countries using excess all-cause mortality: total deaths beyond what’s expected in a normal year. By that measure, lockdown- and mask-eschewing Sweden had one of the best 2020 excess mortality rates in all of Europe—

23rd-lowest out of 30 countries.

(It again trailed Finland and Norway, but a

variety of factors undermine the idea they present a full-on apples-to-apples comparison; what’s more, by some measures, Finland and Norway had even

less stringent policies during the first several months of the pandemic.)

CDC is "Following the TV Pundits"

Vinay Prasad is an associate professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco and co-author of

Ending Medical Reversal: Improving Outcomes, Saving Lives. "Medical reversal" is what happens when new data shows a commonly-accepted practice is not helpful—or is actually harmful.

Decrying the lack of randomized trials backing many Covid-19 policies, Prasad recently

wrote, "When it comes to non-pharmacologic interventions such as mandatory business closures, mask mandates, and countless other interventions, the shocking conclusion of the last 18 months is this:

We have learned next to nothing."

Referring to the CDC’s decision to once again recommend universal indoor masking in areas of higher Covid-19 transmission, Prasad wrote,

"The CDC director calls this 'following the science,' but it is not. It is following the TV pundits."

While declaring his openness to the possibility that masking can be an effective public health intervention, Prasad says

mandates should be driven by evidence—and that the CDC isn’t offering any.

Prasad, who

doesn’t shy away from endorsing coercive government action when he thinks it’s warranted, concludes:

"When the history books are written about the use of non-pharmacologic measures during this pandemic, we will look as pre-historic and barbaric and tribal as our ancestors during the plagues of the middle ages. What the books won't capture is how, in the moment, our experts were simply so sure of themselves."

* * *